what do we mean -

Childhood plays a vital part in this innovative process

We start to develop our imagination and learn to think in childhood, through endless spontaneous play, exploration and creativity -

As we grow up it is easy to lose this connection with our imaginative making and playing childhood experiences.

When doing 'making activities' this energy for ideas can be seen as different steps children go through. A process of observation, experimentation, of trial and error, development and change -

If you really look at what your children are doing you can see what decisions they are taking, the choices they are making, their evaluation of the effect of what they have done, and what physical problems they are trying to solve. You can actually see your child think. If you do this over a period of time you can also see new development and learning as they do things which they have not done before.

This is not apparent if you just look at end results. As adults we have a tendency to take shortcuts -

stages of creativity: looking, thinking, drawing, making, and playing

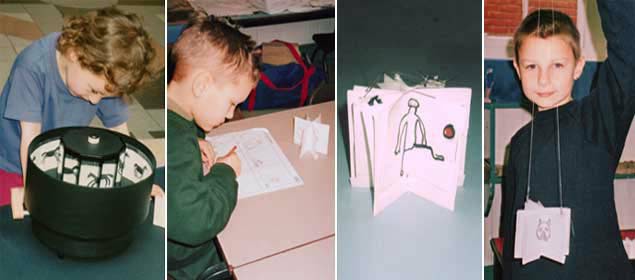

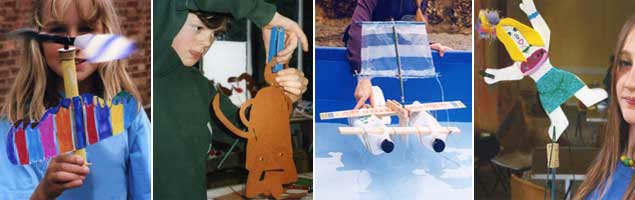

The special nature of 'making things' also allows children to develop a much wider and deeper, tangible experience of the material world. A form of understanding of how things work which is actually very difficult to describe. There are no facts to learn, no one way of doing things, and making mistakes is a necessary part of the activity.

This expertise and understanding is something that can only be acquired by actually making things oneself. It cannot be taught by verbal instruction (although it is helpful to have a demonstration by an adult or to look at what others are doing), but full understanding and mastery of a particular activity can only be achieved by physical action, by doing it yourself. Sometimes you need to keep doing it until it becomes second nature -

The same applies to making activities such as learning to tie a piece of string, or joining two pieces of material together (wood, metal, plastic, cloth), learning how to use tools for cutting, sticking, shaping and smoothing etc. These activities have the added requirement that you not only need to develop personal physical dexterity, but also the tangible results have to function as well. They have to hold together, stand up, or move in the right way.

tangible learning: results need to stand up, hold together, move and perform as expected

General play provides many experiences on this kind of learning -

Richard Gregory says in his BBC documentary ‘Are We Blind To Science?’(broadcast 1989):

"Children are scientists in the making -

who is this? > Richard Gregory

When you learn something in childhood, rather than later as an adult, this seems to offer a level of fluency, quality, speed, and accuracy which is usually lacking when these kinds of skills are learnt later. It seems it is very difficult to achieve this fluency after childhood without earlier experiences to draw on. When experts (in whatever field) are asked about how they came to do that particular kind of work, they always include examples of activities they habitually did as children.

These pleasurable memories are important because they give a sense of familiarity to that particular area of activity. It is a great advantage when starting out as a young adult in the world to have this feeling that you can navigate your way through familiar experiences with some confidence.

These early experiences help to form areas of interest, skill and understanding which can be drawn on later as a basis for future jobs and careers.

what do we mean -

• there is special knowledge and understanding to be gained by making things

• childhood plays a vital part in this innovative process

a historical perspective

• observation, trial and error

• origins of maths

• patterns and geometry

facing the future

growing concerns

• Neil MacGregor

• Sherry Turkle

• Seymour Papert